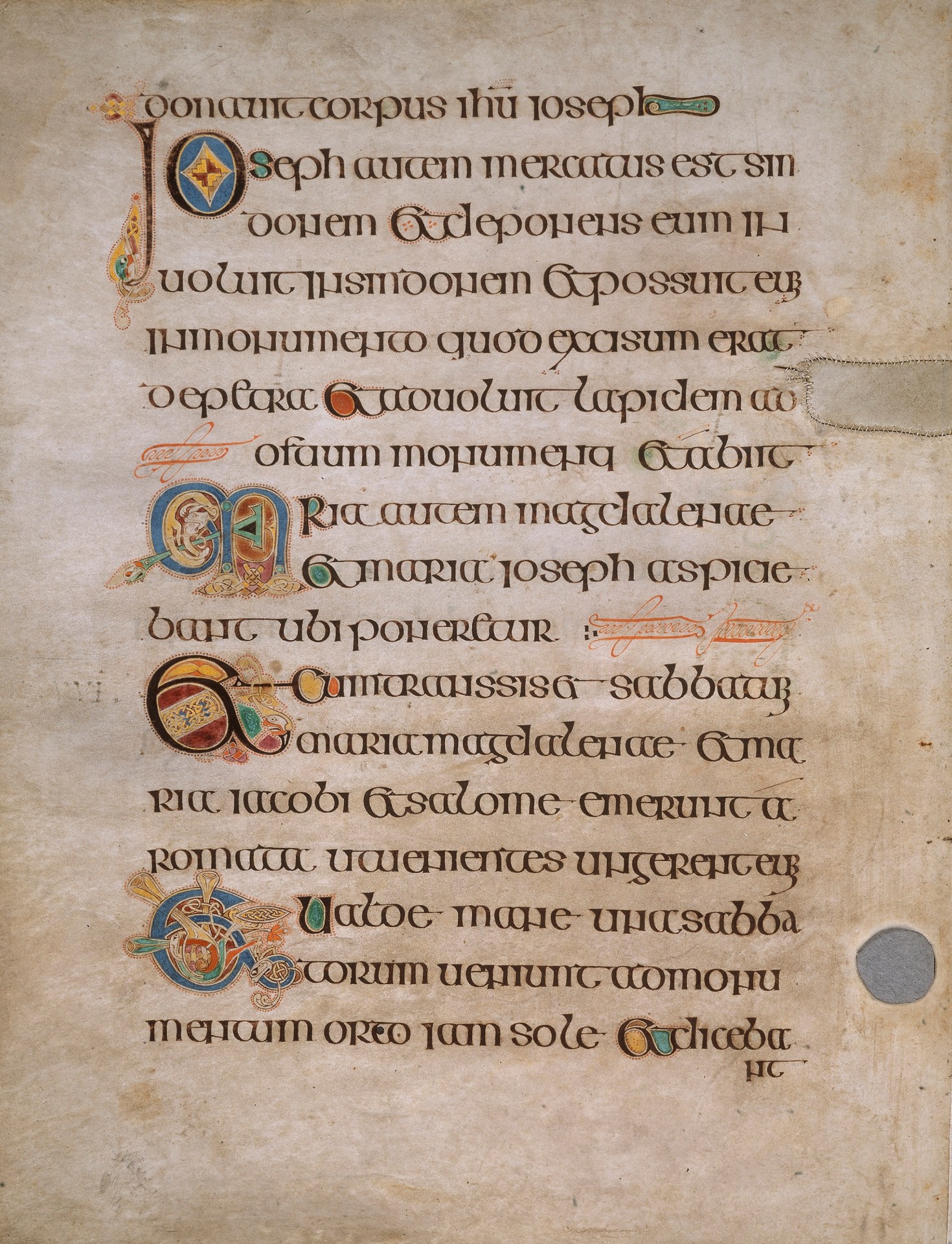

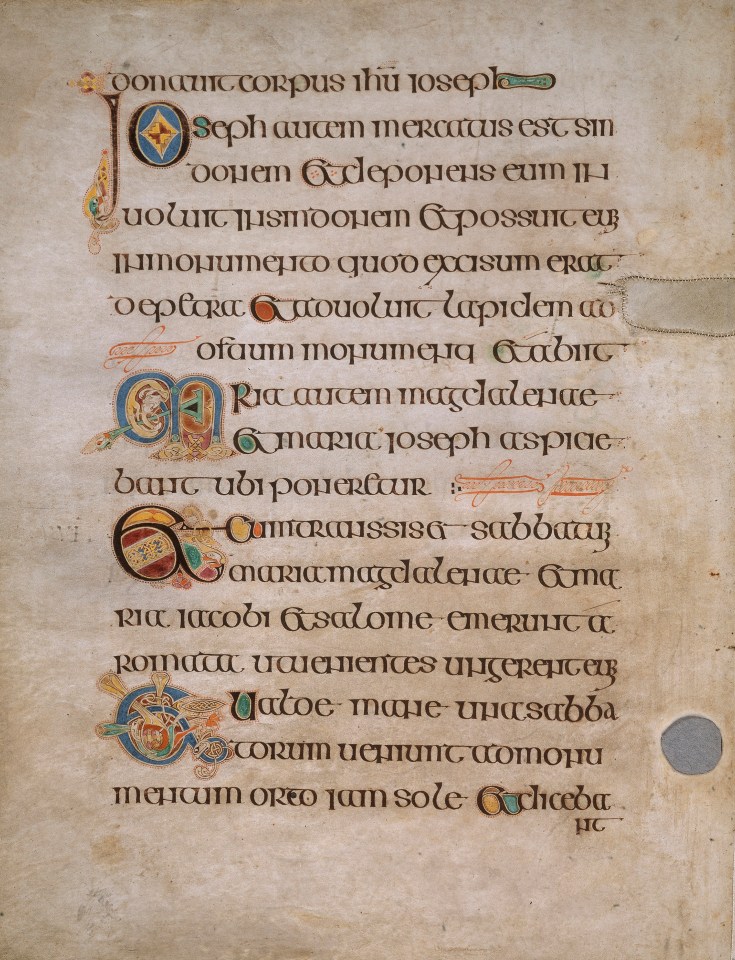

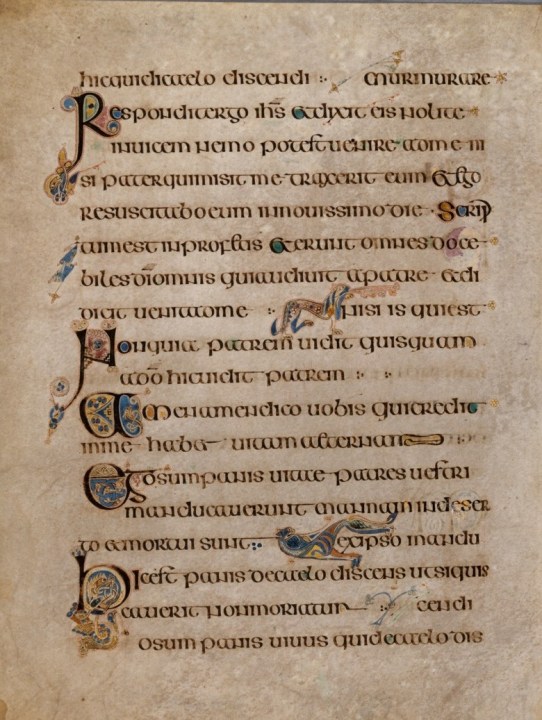

Vellum was a valuable commodity regardless of holes or flaws in the skin. Scribes had to work around holes in the vellum or execute repairs using patches. On the left-hand folio 185v, a patch can be seen stitched carefully around a hole in the vellum. A second hole in the vellum can be observed further along the page. The repair was executed by Roger Powell, a renowned bookbinder who worked on the rebinding of the Book of Kells and the Book of Durrow in 1953. The first hole was repaired as it is close to the edge of the binding and would have placed pressure on the binding structure if left untreated.

In 1568 Gerald Plunket of Dublin added the chapter numbers for the Gospel text – xvi (16) is visible in the margin at line 11 on the left-hand folio, 185v: et cum transisset sabbatum (‘And when the sabbath was past …’) Mark 16:1.

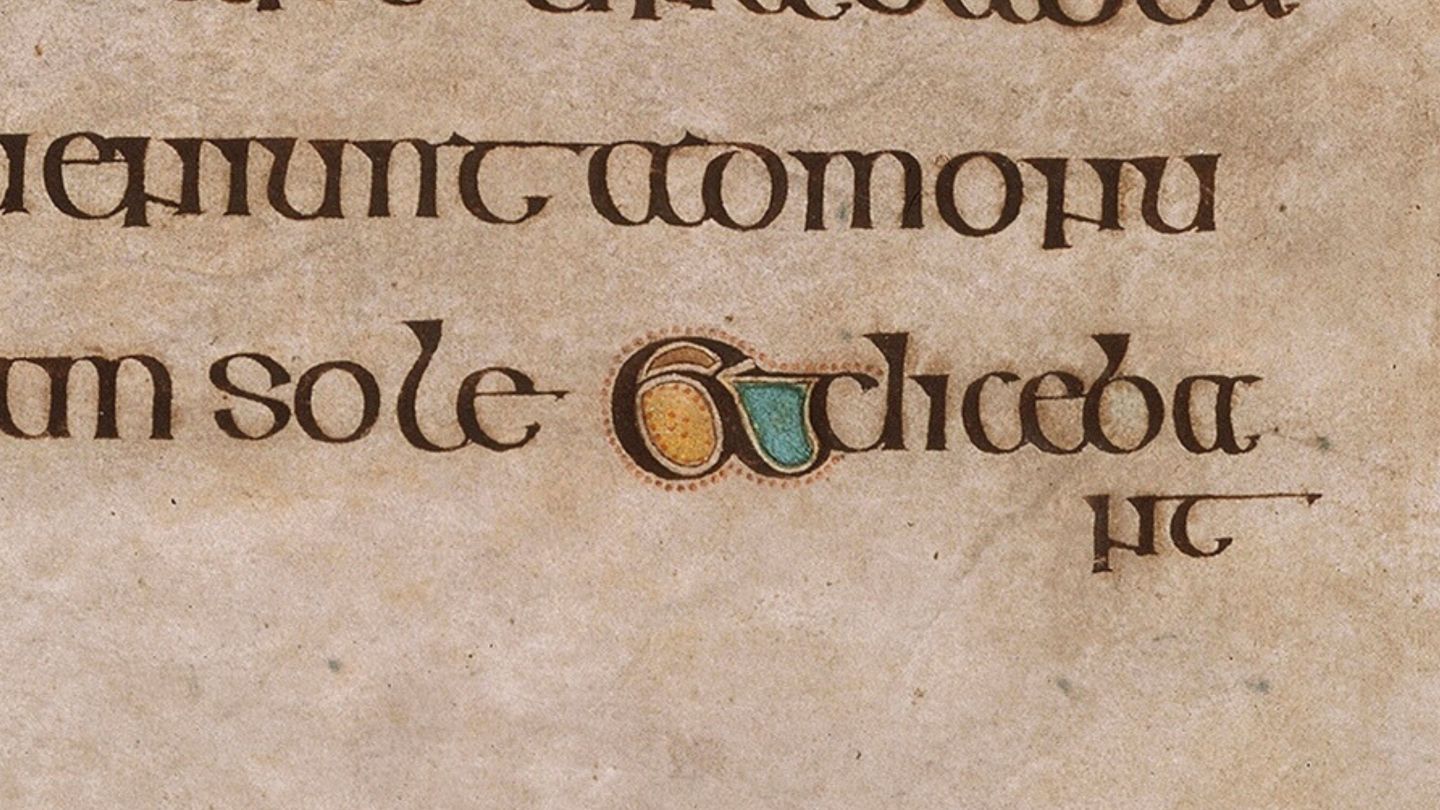

The final word on the left-hand folio 185v is dicebant (‘they said’). Here the scribe has rigidly held to the 17-line format dropping the final two letters (diceba/nt) so they hang below the word. He could easily have accommodated the word on the facing folio, 186r.

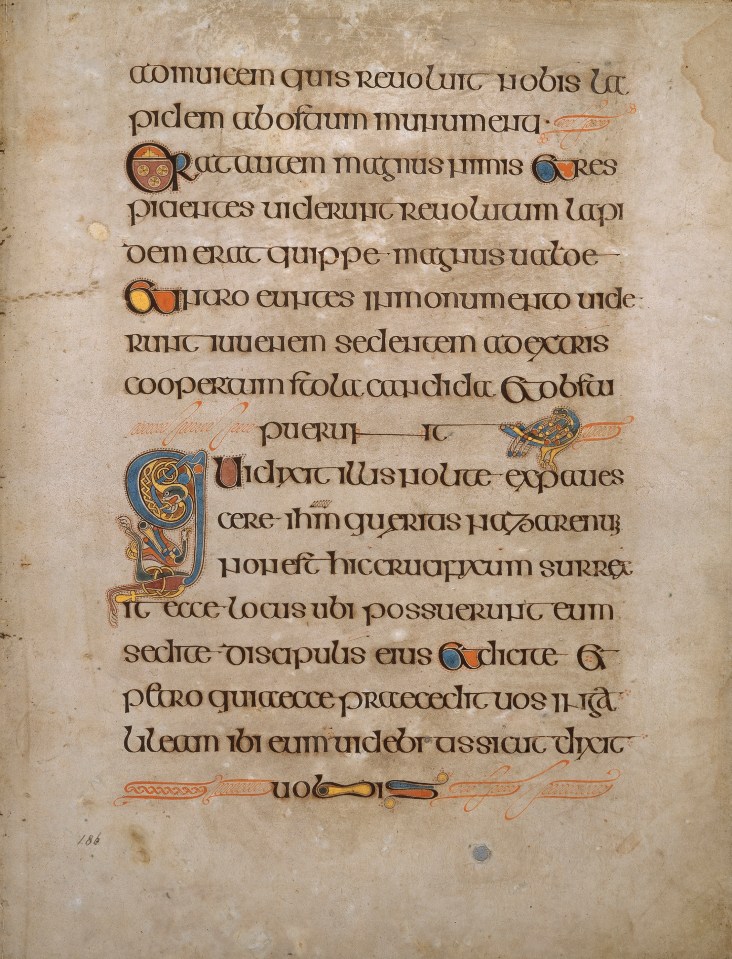

The scribe has again adhered to the 17-line format on folio 186r, this time isolating and elongating single words to fill the allotted space. The word obstipuerunt (‘were astonished’) has been split into two parts: obsti/puerunt straddling lines 8-9.