Pages on display

The current opening of the Book of Kells is the Gospel of Matthew, folios 27v-28r

The current opening of the Book of Kells is the Gospel of Matthew, folios 27v-28r

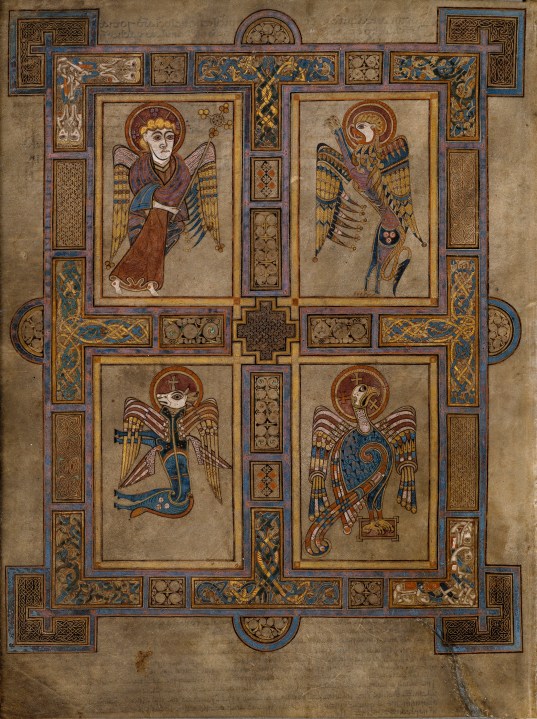

Gospel of Matthew, folio 27v

The decorative plan for the Book of Kells appears to have been that each Gospel opened with a page of Evangelists symbols, a portrait page depicting the Evangelist, and an elaboration of the opening words or letters. It was common scriptorium practice for pages of major decoration to be painted on single leaves, so that the Gospel text could be copied at a faster pace, but single leaves are particularly vulnerable to the breakdown of bindings, resulting in misplacement or loss. The appearance of certain openings today is not as originally intended and it is almost certain that folio 28r was not meant to be blank.

The Evangelist symbols prefacing St Matthew’s Gospel on folio 27v depict the man of Matthew, the lion of Mark, the calf of Luke and the eagle of John. This dates back to the sixth century when Gregory the Great interpreted the Evangelist symbols as the four stages of Christ’s life: Christ was a man when he was born, a calf in his death, a lion in his resurrection and an eagle in his ascension to heaven. Here they are all shown to have haloes and wings, a double set in the case of the calf. The symbol of Matthew holds a flabellum (a liturgical fan), and the eagle clutches his gospel book in his talons.

Close up detail, Gospel of Matthew, folio 27v

The symbols are in framed panels around a cross, with another, stepped cross at its centre. Interlaced snakes writhe in four T-shaped panels at each extremity of the cross. In the corner pieces top right and lower left, a chalice sprouts vine tendrils which are bitten by peacocks. Interlaced human figures are compressed in the corner pieces top left and lower right. In the one lower right, four figures stand within the confines of their frame, their necks unnaturally elongated and their heads hanging down in what may be intended to recall the Crucifixion. In the one top left are four men with red triangles on their cheeks, with knees bent, pulling each other’s beards.

Animal imagery is used throughout the Book of Kells as symbols of Christ to assert his divinity: lions, fish, snakes and peacocks. Snakes within the book have a double meaning. The creatures are usually thought of as representing evil in the world – as in the Garden of Eden – and are synonymous with the devil. However, an alternative meaning can be gleaned from the book’s serpents also, as they shed their skins and renew themselves, which could again represent the resurrection of Christ. Peacocks, too, are integral to the decoration of most of the major pages in the manuscript. They appear at the end of text lines and in prime positions next to images of Christ. They are thought to represent Christ’s incorruptibility or immortality, due to the ancient belief that peacock flesh does not decay.